It’s been a good week for document dumps—especially if you’re interested in surveillance policy. On top of Chris Soghoian’s revelations about telecom location tracking requests and a slew of leaked telecom and social networking site surveillance manuals for law enforcement at Cryptome, I’ve also been poring over the FOIA documents on cell phone lojacking obtained by the ACLU. Like a lot of the stacks of papers that pile up on your desk when you study national security surveillance for a living, these are heavily redacted, and over time, you start developing little heuristics for trying to put the puzzle pieces together, to at least limit the domain of what might be in those black boxes. What can context tell you? What can you infer from the length of the redacted material? Looking at these sets of documents, I think I may have picked up on an interesting variation on Mike Masnick’s “Streisand Effect”—that now-familiar phenomenon where efforts to suppress information end up drawing all the more attention to it. Here’s a partly redacted footnote that leapt out at me from a template application for a cell-tracking order from Nevada:

At first, I was just irritated. What bonehead had redacted this? They’d cut out the statutory definition of “basic subscriber information” found in the U.S. Code! Even if you don’t happen to have §2703(c)(2)(E) seared into your memory, the citation to the law is right there! The missing bit reads:

(E) telephone or instrument number or other subscriber number or identity, including any temporarily assigned network address; and

What sort of jackass (I fumed) had concluded that the contents of American public laws were some kind of operational secret? But of course, once I got over my pique at this obnoxious excess of secrecy, I started thinking: Why, exactly were they worried about someone reading that? I had, perversely, just gained a bit of new information. Not the statutory definition—that was already sitting on my desk in yet another pile—but the fact that the investigative technique they’re taking pains to conceal (that’s what “b7e” means, it’s the code for the FOIA exemption they’re invoking) involved exploiting that part of the statute in some crucial way.

Now, this was not exactly an epiphany. This is, after all, a model application for getting cell site and sector information to reveal location, and knowing what kinds of orders they typically use to get this information, I had figured they would invoke the part that enables them to request a “temporarily assigned network address.” But it does point toward the larger problem—or strategy for reading, if you spend your time outside the federal government poking through this stuff—that I want to call the Redactor’s Dilemma.

Imagine you’re given the task of censoring documents like these for public release. There are some bits that you just obviously cut out—whole paragraphs describing operational details that, for good reasons or bad, you want to keep secret. But that won’t be quite enough. Because you’re probably going to have folks reading the documents who know a little something about the law, a little something about the relevant technology, and a little something about surveillance tactics generally. Folks who might piece together one of those facts you’ve excised, not from an explicit statement, but from individually innocuous clues that would nevertheless reveal something if an attentive reader pus them together in the right way.

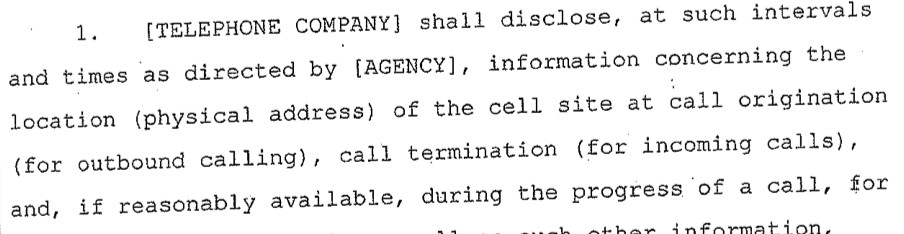

This is where the dilemma arises. Because if anyone does happen to determine, by other means, what lies behind one or two of those black boxes, you’ve actually given them a much bigger clue. You’ve pointed them to the precise facts that, assembled in the proper order and with the right background knowledge, hint at what you were trying to hide—facts they might otherwise have skimmed over without a second glance. But it’s worse than that, even. Because the facts really are more or less innocuous in isolation, a lot of that information won’t be secret per se. The choice of just which lines to redact involves a fair amount of imaginative guesswork—which bits might a reader combine in a chain of inference? That means if similar documents are being censored by different redactors, you’re apt to get the worst of both worlds—many pieces of the puzzle left exposed in one document or another, sufficiently parallel in structure to make them mutually completing, with the potential significance of each one highlighted by its absence from the others. Compare, from the Nevada template:

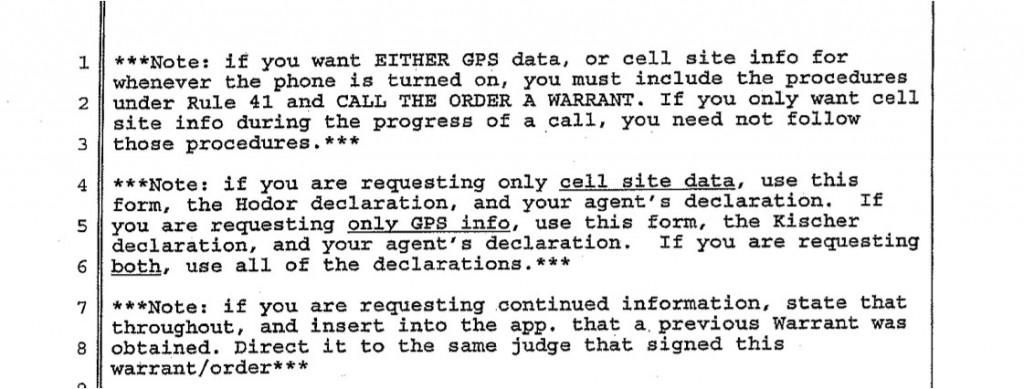

And now, from a similar template used in California:

And now, from a similar template used in California:

Now compare these two, both from the same California dump, but presumably redacted by different hands, judging by the handwriting marking the excised bits in each:

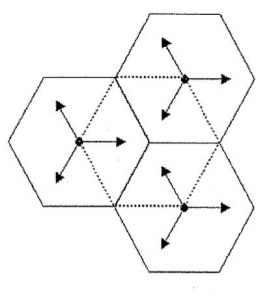

Now, the question again, what are they worried someone might pick up on? The fact that they can track the phone whenever it’s on with a probable cause warrant? Seems unlikely. It really looks like they’re skittish about what someone might infer from the fact that they get cell site/sector data while the call is in progress, not just at the beginning. But why is that important? Here it does help a bit to turn to that “Hodor declaration” they mention—the unredacted parts, anyway. It’s a convenient primer on the ins-and-outs of cellular telephony, the gist of which is to reassure the judge that mere cell site/sector data (1) is ordinary addressing information the telco has to record anyway for their own routing purposes, and (2) is really quite vague location data, not nearly as precise as you’d get from GPS or even the cell tower triangulation methods some phone companies use to provide location-based services. (If you have a first-gen iPhone, that’s how the pseudo-GPS works; later models have real GPS.) Now, that’s important because for that really precise location information, they get kicked up to the much more onerous restrictions that apply to tracking devices. That vague cell site information? Practically a rubber stamp—they just need to certify “relevance” to an investigation. Ah, but what if they can turn that vague information into something a little more precise, even without the multi-tower timing data the telcos use for triangulation? Again, Hodor’s “declaration” here is helpful. Here’s a crude diagram of how mobile networks work:

The solid hexagons are the “cell sites,” each with a tower at the center. Each arrow is a “face” defining a 120-degree “cell sector.” The central hex in dotted lines, defined by the overlap of the surrounding sector borders, is the actual “cell.” Even in an urban area, where each cell radius might be a few hundred meters, if you’re just getting the receiving cell tower and face, you’ve only narrowed your target’s location down to a sector—in the vicinity of a few city blocks at best. [Note: Not sure whether this was my misreading or an error in the document, but a correspondent says I originally flipped the definitions of “cell” and “cell site,” now fixed.]

The solid hexagons are the “cell sites,” each with a tower at the center. Each arrow is a “face” defining a 120-degree “cell sector.” The central hex in dotted lines, defined by the overlap of the surrounding sector borders, is the actual “cell.” Even in an urban area, where each cell radius might be a few hundred meters, if you’re just getting the receiving cell tower and face, you’ve only narrowed your target’s location down to a sector—in the vicinity of a few city blocks at best. [Note: Not sure whether this was my misreading or an error in the document, but a correspondent says I originally flipped the definitions of “cell” and “cell site,” now fixed.]

Now let’s go back to thinking about why it’s so important that they get additional addressing information—still, by hypothesis, just site/sector (or tower/face) information—while a call is in progress. We’ve got two distinct documents where (one assumes) two different censors thought that ought to be redacted. Well, that information would be recorded, as Hodor explains, when the system “hands off” a call from one tower to another. Partly it knows when to do this because it’s also measuring signal strength, but assume you’re not getting that; just tower/face updates. Well, at the moment of that handoff, or when the “face” changes, suddenly your location range just got a whole lot smaller: You know your target is somewhere along the border of two cells or two sectors. Now suppose your site/sector changes again—you’ve got a vector! A third crossing and, given either a streetmap or the assumption that the target is moving roughly in a straight line, and you can start making educated guesses about your target’s speed and trajectory. Two handoffs in quick succession suggests he’s moving through a cell near the vertex; a longer gap suggests he’s closer to the center.

Now, did this possibility first cross my mind when I looked at these documents? No, not really—but thinking about this stuff breeds paranoia, and so a lot of possibilities cross my mind. The pattern of redactions above make me a good deal more confident that this is probably a popular method of getting moderately detailed location info on the “cheap” in terms of legal process. In the criminal context, anyway—for intel, who knows. They make it explicit in some of these documents that the Justice Department’s legal position is that they can get realtime full-GPS with a mere “relevance” court order, but they go ahead and apply for that kind of tracking under stricter rules because they don’t want to risk suppression. Probably they’re less worried about that when they’re operating under FISA pen/trap orders. But if this is right, they may be pulling a bit of a fast one on judges here. Because a lot of these applications to judges—and certainly the Justice Department’s legal briefs in the cases where courts have been reluctant to approve tracking on such a loose standard—imply that this cell site/sector data, why, it’s so rough and approximate that it barely counts as tracking at all. Certainly, at any rate, it’s not so precise as to invade any sort of privacy interest. Except that for a target in steady motion, it begins to seem as though they can probably get a substantially more precise fix.

This is a bit speculative, of course—I might be wrong, or maybe this is all old news to people who focus intently on location tracking, and I just haven’t seen the document where it’s all spelled out explicitly yet. What’s more interesting to me is the method… a method that also, alas, suggests a limit to crowdsourcing with these document dumps, since it depends on the person who sees information in the clear in one document recognizing that it’s probably the same text that was redacted in another. Harder, but not impossible, for a swarm tackling a docdump in small pieces: It might mean that swarm analysts want to summarize redacted bits no less than the contents of the documents they read, so that their teammates can spot the other places where the blanks are filled in.

Addendum: Apparently my own prior reporting on this slipped my mind. The further reason this might be useful is that if you can get a reasonable idea of the trajectory of a target in motion, you can get close enough to use a triggerfish-enabled van to home in precisely. As Ryan Singel at Wired has reported, it works roughly like this:

- FBI agents investigating a case prepare a court order saying a cellphone number is likely relevant to an ongoing investigation, and a judge signs off on it.

- The court order is faxed to a mobile carrier, which then turns on surveillance in its switches, and begins delivering call data and cell site information to the FBI’s DCS 3000 software.

- That software keeps track of which cellphone towers a phone uses or pings. A central FBI database translates a mobile carrier’s cell tower code to latitude and longitude coordinates.

- The software sends the coordinates to the agents and technical personnel in the mobile unit who then drive to the general area. But since cell tower information is not precise, agents in the van use antenna array connected to tracking software to zero in on the cellphone.

This is actually somewhat less troubling, because it doesn’t sound like the sort of thing that could easily become a routine practice— it’s got to be important enough to find this specific guy right now that you’re going to send a van full of agents chasing after him. But clearly you’d need the realtime data to make this method feasible; otherwise your target is likely to be out of range by the time your tracking team gets to the original location.

12 responses so far ↓

1 Jacob Wintersmith // Dec 8, 2009 at 4:47 pm

If I were a redactor, after I had cut out everything in a document I thought needed to remain secret, I’d make a second pass to redact a bunch of random passages.

2 Ruling Imagination: Law and Creativity » Blog Archive » Interpreting, accurately, what isn’t there — the Redactor’s Dilemma // Dec 11, 2009 at 10:03 am

[…] as telling as what we typically think of as “facts.” Julian Sanchez, in a post entitled The Redactor’s Dilemma, gives a brilliant demonstration of this truth. Sanchez has been “poring over the FOIA […]

3 Links 11/12/2009: French Military on Thunderbird | Boycott Novell // Dec 11, 2009 at 1:14 pm

[…] The Redactor’s Dilemma What sort of jackass (I fumed) had concluded that the contents of American public laws were some kind of operational secret? But of course, once I got over my pique at this obnoxious excess of secrecy, I started thinking: Why, exactly were they worried about someone reading that? I had, perversely, just gained a bit of new information. Not the statutory definition—that was already sitting on my desk in yet another pile—but the fact that the investigative technique they’re taking pains to conceal (that’s what “b7e” means, it’s the code for the FOIA exemption they’re invoking) involved exploiting that part of the statute in some crucial way. […]

4 The Volokh Conspiracy » Blog Archive » The Redactor’s Dilemma // Dec 22, 2009 at 2:50 am

[…] Sanchez recently offered up this very interesting post on ways to figure out what the redacted version of released government documents may say — at […]

5 TruePath // Dec 22, 2009 at 6:13 am

Your comment about the handoffs narrowing the region doesn’t really make sense.

After all the handoff is made based on the signal strength at the various cell sites, exactly what you already have access to, so a handoff shouldn’t help to locate the cellular device any better than the signal strength info.

—

Now true the agencies can’t actually have someone randomly cut out extra passages to stymie this kind of analysis but they can do something which might be even more effective. Let total morons without real power or operational knowledge do the redaction so you have no idea if this is a significant redaction or simply something redacted because the redactor was confused or covering their ass on a subject they didn’t understand.

6 The Redactor’s Dilemma | Liberal Whoppers // Dec 22, 2009 at 7:17 am

[…] Sanchez recently offered up this very interesting post on ways to figure out what the redacted parts of released government documents may say — at least […]

7 Belligerati // Dec 22, 2009 at 11:54 am

[…] Sanchez in The Redactor’s Dilemma make an interesting point about redacting information that I hadn’t considered, that how you […]

8 Douglas2 // Dec 22, 2009 at 11:25 pm

Perhaps they should declare death to all modifiers on one day, remove every adverb and every adjective the next. Then for another document they can have a war on articles.

9 m65 // Feb 16, 2010 at 6:50 am

good read thanks for the share. i really like the way the article is written and also the design of the website

10 Is the Concept of Anonymity Lost? « Rejuvyesh Spricht // Mar 3, 2012 at 6:55 am

[…] On the other hand, if you are on social networks like Facebook and Twitter, or even have a Google account, then there is nothing one can do ward of attacks on your privacy (Except maybe deactivating those moronic accounts, even though your personal data attached to it would never be promptly deleted). Researchers have found that even actively anonymized data in public data-sets such as your Amazon purchases. These attacks don’t exploit the observation that the choice of what data to remove is as interesting as what is left, what Julian Sanchez calls “The Redactor’s Dilemma”. […]

11 google plus account login // Sep 8, 2014 at 1:59 am

Woah! I’m really loving the template/theme of this blog.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s tough

to get that “perfect balance” between superb usability and visual appearance.

I must say you’ve done a awesome job with this. Also, the blog loads extremely fast for me

on Firefox. Excellent Blog!

12 www.couplesshowerinvitations.info // Oct 20, 2016 at 7:24 am

I have a dream that one day … the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.