Marc Ambinder notes that the federal government’s annual wiretap report—that’s Title III criminal wiretaps, not the foreign intel surveillance covered by FISA— is out, and the headline figure is that there was a 16 percent decline in wiretap orders over the previous year. Then he offers some speculation on why this might be that makes me wonder whether he made it past the headline:

Marc Ambinder notes that the federal government’s annual wiretap report—that’s Title III criminal wiretaps, not the foreign intel surveillance covered by FISA— is out, and the headline figure is that there was a 16 percent decline in wiretap orders over the previous year. Then he offers some speculation on why this might be that makes me wonder whether he made it past the headline:

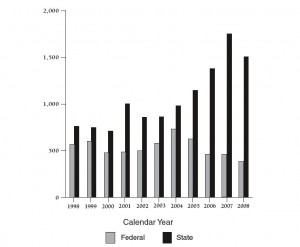

The big headline: the number of wiretaps dropped 16% to 386 in 2008 as compared to 2009. State-agency authorized wiretaps — by far the majority — dropped by 14%. It’s hard to figure out what accounts for such a large decline, although I’m guessing that the increased scrutiny by Congressional Democrats of intelligence gathering procedures contributed to pressure on criminal agencies to make sure they were complying with the letter of the law.

First, I didn’t notice all that much increased scrutiny from congressional Democrats—maybe he means “short-lived token resistance to massively expanding intelligence gathering powers”? Even if this scrutiny were real, it’s supposed to have had its most pronounced effect on… state law enforcement agencies? Whaa?

Take a glance at the handy dandy chart above, and you may detect a more plausible explanation: This profound “decline” at the state level was from the highest number of authorizations in a decade to the second highest number in a decade. They’re still up significantly over 2006, and combined authorizations are up a whopping 42 percent since 1998. Oh, also? These figures are based on reporting from only 22 states, compared with 24 in 2007, and there are always reports that come in late, so it’s entirely possible this is just a question of the numbers being in the mail. Finally, notice that the “hit rate” of the wiretaps seems to be dropping off: 30 percent of intercepts were incriminating communications in 2007, but the ratio fell to 19 percent in 2008. The vast majority of taps are used in drug cases, so if dealer behavior is changing in ways that make wiretaps less useful—increased use of temporary “burner” phones for conversations about illegal actions, say—that might well explain decreased reliance on a costly technique: State wiretaps averaged over $40,000 a pop.

Federal wiretaps, however, aren’t just down relative to last year, but appear to have hit a ten year low, though the absolute number there is clearly a good deal smaller. Maybe here’s where that “increased scrutiny” had its effect? Well, maybe. I’m inclined to wait for the 2008 FISA report to Congress, which should be released sometime fairly soon. But if you look at the chart for FISA orders granted annually through 2007, you’ll notice that in recent years there have been many times more of those issued than federal Title III wiretap orders.

Federal wiretaps, however, aren’t just down relative to last year, but appear to have hit a ten year low, though the absolute number there is clearly a good deal smaller. Maybe here’s where that “increased scrutiny” had its effect? Well, maybe. I’m inclined to wait for the 2008 FISA report to Congress, which should be released sometime fairly soon. But if you look at the chart for FISA orders granted annually through 2007, you’ll notice that in recent years there have been many times more of those issued than federal Title III wiretap orders.

Recall also that, with the complicity of those eagle-eyed congressional Democrats, the executive branch has, since the summer of 2007, enjoyed discretion to authorize targeting of persons reasonably believed to be overseas without the burden of obtaining prior authorization from the FISA court. That power is not limited to investigations aimed at hunting down terrorists, but applies in any case where its thought that an intercept might contain foreign intelligence information. “Foreign intelligence” is construed as encompassing the activities of international narcotics operations—again, remember, the vast majority of criminal wiretaps are obtained as part of drug investigations. Finally, since we’ve done away with that pesky “FISA wall,” information gleaned from FISA intercepts can be used in domestic criminal prosecutions.

Madness, you say! These expanded powers were just so we could listen in on Osama bin Laden’s daily phone calls to Omaha! Naturally. But I’ll confess I would not be completely astonished if, under the new legal regime, some proportion of federal drug investigations hadn’t increased their reliance on intercepts from the overseas associates of domestic drug criminals, whose communciations would require a Title III warrant for a direct intercept.